IFN Committee Update Dec 2023

A Significant Date for your Diaries

As we come to the end of another year, we want to wish all our members and followers a happy and peaceful Christmas and all that is good for the New Year. We are grateful for your continued support.

2024 approaches and with it our AGM, which will take place on Wednesday 24th January 2024 at 7.30pm. We hope that many of you can join us as we plan for the year ahead. This AGM will be a significant one, as it marks the end of term of the current organising committee. Some members of the committee have generously agreed to continue, but it’s also important to ring the changes and invite some new energy.

The Network is maintained through the efforts of our volunteers, the people who host our online sessions, the team who work to create these Newsletters to keep us connected and informed, members who have contributed to our in-person gatherings, and those who led us in a wonderful series of online workshops, Elaine and Marie who have offered bi-monthly Focusing and Poetry workshops, our podcast team and the committee. (Actually, there’s one person who has done ALL of those things – guess who?) We are indebted to all our volunteers for their tireless and generous contributions to keeping the show on the road.

As we move forward, we invite you all to think about how you might like to be involved with the Network, whether that’s as a member of one of the existing groups or by creating an entirely new initiative that would support or promote Focusing in Ireland.

We’ve come a long way in the past three years and we have no doubt that even greater things are possible as we move forward. So please join us for the AGM and bring along your suggestions to help us grow.

Some policy clarifications:

In response to issues that have arisen over the past months, we think it might be useful to clarify the Network’s policy in a few areas. We hope you understand the need for these.

In relation to our booking and refund policy: Booking for all events and courses will close 48 hours before the start date. IFN reserves the right to alter or change the programme or cancel events if necessary. Where numbers are small, events may not be sustainable. In the event of cancellation by the Network, a full refund will apply. If an event is re-scheduled, registered participants, who cannot attend as re-scheduled can request a refund. Online workshops are fund-raisers for the Network and payment for these is non-refundable.

Booking for our in-person gatherings will close at midnight on Wednesday prior to the date of the gathering. Cancellations for the in-person gatherings – a full refund with seven days notice. Since some centres require payment in advance for both venue and food we may need to retain the cost of meals where this applies.

In relation to advertising: Only focusing related events and courses will be promoted by IFN and advertised on our media outlets.

Profile members are invited to advertise their courses on the IFN website and through the quarterly Newsletter. Details should be sent to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Members are also encouraged to post their courses on the IFN Facebook members group.

An experiential "turn" in poetry

An experiential "turn" in poetry

The turn towards the body happens to every human being but in very exceptional circumstances the symbolization of the experienced sensation occurs through speech. Nevertheless, the verbal unification of the outer world with the inner body has always been present, though not frequent. He who has no contact with the body will not attempt to symbolize the subtle and indistinct experienced sensation, but he will symbolize occasions when the body 'cries out'. Usually symbols are chosen which are already common such as 'butterflies in the stomach', 'something heavy in the chest' and 'a knot in the throat'.

The turn towards the body is found in many poems. In contrast to the turn towards the body as mentioned above, poets symbolize more subtle sensations. Possibly it was at some point their own experienced sensation that took on the symbol they offer us through their poems.

The outer world may have been described by the first poets, but the inner body is a field which is quite virgin in terms of the symbolization of the phenomena that govern it. For example, the lyrics of Alexander Pushkin:

'If you but knew the flames that burn in me which I attempt to beat down with my reason.'

They describe well the experiential process of every human being who would like others to be able to perceive what is happening inside them, but at the same time has enlisted logic and tries to suppress this experience.

The Greek poet Dionysius Solomos also in several of his verses turns the attention of either his own or the heroes he describes towards the body. Here, in a verse from Free Besieged he turns our attention to the body of the hero whose courage is symbolized by the image of the angry sea:

My gut and the sea never rest

Charles Bukowski's poem "blue bird" takes us inside the body where he describes his relationship with the experience of the bird that he often feels in the place of his heart. Within the poem there is a conversation with the blue bird, to whom the poet admits that he treats it cruelly and does not allow it to free itself because he is afraid of it, in particular he fears that if he frees the blue bird, it will ruin his success in Europe(!), he plies it with whisky to calm it down and only releases it when everyone is asleep. At the end of the poem and in the piece I quote he admits that this experience sometimes makes him cry. The poem is quite reminiscent of the symbolization of the inner world. It is possible, of course, that the blue bird refers not to a single experienced sensation but to all that is happening inside the poet's body:

then I put him back,

but he's singing a little

in there, I haven't quite let him

die

and we sleep together like

that

with our

secret pact

and it's nice enough to

make a man

weep, but I don't

weep, do

you?

The experiential "turn" in songs

The turn towards the body, towards inner experience and the symbolism of experience within the body is very common in the lyrics of songs. Often they blend wholes that happen outside by taking them inward, as in the song ‘Prigipessa’ that the lyricist takes us from the outside world to his "inner home":

Outside the wind blows and yet inside me,

Inside this house, my princess,

your light and the light dance around us

unbelievable is our world and our character.

Also noteworthy is the song "Andromeda" where the lyricist chooses to create through the poetic images he gives us a journey that starts from the fiery center of the earth, passes through the constellation of Andromeda and ends up on the surface of the earth but before that he makes a "pause" in his inner body where he describes to us in a poetic way what happens there:

Deep there, deep, deep in my gut

there's something going on, lady

A thousand horses are turning blindly

And they're asking for an exit and they're chasing me.

The list of poems and songs that refer in an experiential way to "something there" happening in the body of the poet or lyricist is inexhaustible. There are folk songs and even pop songs that attempt this inward turn. My own judgment is that the songs and poems that attempt this are quite beloved and leave a lasting mark on the art.

Clearly this proves that the turn inward is something natural, something that is experienced by everyone regardless of educational level, and it is something that touches the sensitive chord found in every human being even in the most popular, the most general audience. I'll close the list with the lyrics of a song that apart from drawing attention inward, to the body, maintains it throughout its lyrics:

I've got a tiger inside me wild and starving

That's always waiting for me and I'm always looking for her

I hate her and she hates me and she wants to kill me

But I hope we will be friends in time

She's (the tiger) got teeth in my heart and claws in my mind

And for my own sake I'm fighting for her

And all the good things in the world make me hate her

To sing to her the heaviest of sorrows

She (the tiger) pushes me over mountains, valleys and cliffs

To embrace her in the craziest dance

And when the nights are cold she remembers her cages

she gives me her coat to wear

Sometimes we get drunk and fall down

Almost loving each one to sleep

And this silence is like the silence just before the storm

like the last hour when she will attack.

Here it should be made clear that what these songs and poems are doing is not necessarily describing the listener's felt sense. It is not even certain that the poet as he wrote them was constantly in touch with his own felt sense. But what they certainly accomplish is the experiential description of an experience. According to Gendlin this process is what can make any approach therapeutic, so why not art?

One could of course ask whether there is poetry and art that is not experiential. In the sense that Gendlin defines the word "experiential", that is, one that turns towards the physically focused experience, the answer is that there is art that keeps the reader in the "head". Without diminishing the value of this art I will give an example from Antonio Porcia's poetry collection "voices". In voices there is no reference to the inner, bodily experience. Yet there is a strong sense of experientiality but not in the way Gendlin defines it: it is a collection of extremely short poems which show that the man who wrote them looked at his experiences with a very deep eye. An example is the following:

When it seems to me that you hear my words, it seems to me that my words are yours, and then I only hear my words.

With these lines the poet shows us in a very person-centered way how two people interact in a relationship through speech. Perhaps the deepest point of understanding of each other is when “what you said" and "what I said" become what "we said". Clearly, there is no attempt to turn to the body through these verses, as there is through all the other poems in the collection.

Lets now return to the F.O.T. approach. Efficient response is one that aims to make contact with "that" from which the client is speaking. We can see that the verses I mentioned above accomplish this to a certain extent. They certainly speak of the poet's experience, but the moment they "touch something" to the reader, if anything, they at least help the reader to turn inward. They also bear a strong resemblance to the experientially focused conversation that can take place in an F.O.T. session. The fire in the chest, the bird that chirps and demands at the same time, the guts that never rest, the blind horses looking for an exit, the dancing light, the tiger that I fear will attack me, all of these expressions are like something out of a Focusing or F.O.T. session. In particular, Purton uses a similar image in a session excerpt he provides: A snail curling up the moment the client tries to get close to it and talk about it.

Gendlin himself uses the example of a poet trying to complete a poem but cannot find the last line. He acknowledges that he has a "feeling" about what the last line should be, but he does not yet have the words to express it. This sense is vague and guides the poet in finding the right words to complete the poem. This process is similar to what happens in psychotherapy, where patients look for words to express their feelings and deal with their problems.

Poetry, this art of creative curiosity, tries to identify pre-conceptual parts of the world and give them a symbol. Since it has now assisted in the symbolization of the whole external world and in the creation of abstract concepts, it enters the body and meets the therapeutic process there to such an extent that their utterances now coincide.

Kostas Mavromatakis

Three Assertions About the Body, by Eugene Gendlin

A personal review by John Keane

Many Focusers encounter a difficulty in sharing the “idea” and “experience” of Focusing with friends, family, and colleagues. It is my hope that this review will help in this respect.

Most people know Eugene Gendlin as a psychologist, what some may not realise is that he was first a philosopher. As such he was well versed in the how language functions in human interactions.

So, let us dip into his sense of “what” a body is, and how we can have bodies that are not just physical structures but can connect us directly to our lived experience.

Gene opens this paper with a provocative question “How is Focusing theoretically possible?” And if you are familiar with Focusing you will know this is not an easy question to pose. So, Gene wonderfully sets out his agenda to explore this in terms that people unfamiliar to Focusing may appreciate. As such he points towards bodily sentience as an essential part of the human experience. It is not something we add on – it is already there, but Focusing gives us direct access to it. Gene tells us that “Everyone has at times had it, and yet-isn’t this odd?--hardly anyone talks about it. Our language has no name for it.”

Let us explore how Gene offers to describe the human body in a way that makes Focusing possible.

He begins with intuition or what we might call a hunch. Intuition/hunch points towards something important that emerges in our living, but we cannot explain how this emerges. Gene wants to explore this kind of emergence, this kind of experience.

“To think further about how Focusing is possible, we have to think differently about the living body. So it is important to notice that when we talk about Focusing we use the word “body” in a certain way: We use it to talk about how we feel our bodies from inside.”}

1st Assertion about the Body – The Body Knows the Situation.

This leads Gene to introduce his first assertion about the body – the situational body – an assertion that “the body knows the situation!” There is a novelty in this assertion because many people think that we know the situation and the body simply reacts to this knowing, and of course that is true to some extent, but our bodies can also feel the situation directly.

“For example, you see someone you know on the street but you don’t remember who it is. This is totally different than seeing a stranger. This person gives you a familiar feeling. You cannot place the person, but your body knows who it is. What is more your body knows how you feel about the person. Although you don’t remember who it is, your felt sense of that person has a very distinct quality… Any other person would give you a different body-sense.”

Gene insists that to explain this kind of experience we need to allow the experience itself to function/work in our explanation. To enable this experience to function/work in this way we need a kind of thinking that has the following characteristics:

- “The experience is felt rather than spoken or visual. It is not words or images, but a bodily sense.”

- “It does not fit the common names or categories of feelings. It is a unique sense of this person or this situation.”

- “Although such a body-sense comes as one feeling, we can sense that it contains an intricacy”.

Setting out the characteristics of the situational body in this way allows Gene to offer us a new kind of bodily concept – “implicit intricacy”. The body sense that forms in the context of a given situation contains many strands or parts that are not immediately identified separately but emerge at first in one sense.

So, if I have an argument with John, the bodily sense that emerges has an initial complexity that may not first be clear. If we “open it and if we enter, we can go many steps into it.” The initial anger that first emerges may hold an implicit (not initially clear) complexity about all of the arguments I have had with John, about other arguments that have a similar kind of pattern, and perhaps more patterns or strands may emerge from earlier experiences. An implicit intricacy emerges that contains all about that kind of experience.

Having introduced this kind of “implicit intricacy” Gene can now proceed to consider the situational body as an interaction with its environment rather than something separate. The implicit intricacy becomes a doorway through which we can enter deeper into our situational experience – allowing us to separate out the strands of that experience. This opens up the richness and relevance of any kind of experiencing. As we dance with our experiencing in this way, we discover that things and circumstances are no longer just out there and unchangeable, rather experiencing can be lived forward and elaborated.

2nd Assertion about the body – We Have Plant Bodies

I remember the first time I heard this assertion; I thought that Gene had lost the plot! What was he talking about? Gene is very clever in how he offers new concepts and ideas. He is careful not to phrase them in language that could lapse back into a different kind of understanding. He is very clear about what he means and wants us to follow him in this way. The assertion about our plant bodies invites us to open up what we mean by the body in a new way.

“How can the body know our situations and know them more intricately than we do? And how can it project new ways of action and thought?”

It is commonly thought that the body can only know what it perceives through the 5 senses. A plant does not possess the senses that we have, and it doesn’t need these senses to garner information about its living. A plant is an interaction with its environment. It knows how to turn towards the sun, how to feed from the soil and water and how to synthesise sunlight. It organises and makes itself in and with its environment.

“Animals live more complex lives than plants.” And animals have the kind of information that plants have. Animals organise and makes themselves with and in its environment. For animals the plant body information is elaborated by the 5 senses. These senses give the plant body (of the animal) more information about the environment, this feeds into the complexity of how the animal interacts with its environment.

The human body has all of the complex interactions with its environment that the plant body and animal body possess but with the added complexities of language and culture.

“Language and culture greatly elaborate the life-process and the information of our plant bodies. My second main point is: We can think of our linguistic and situational knowledge not as separate and floating, but as elaborations of our already intricate plant-bodies.”

OK, there is a lot in this quotation, so perhaps we can open it up to sense what that means to us.

We have plant bodies that are an interaction with our environment, we organise and make ourselves in and with the environment. Without sunshine or water – there is no plant, without oxygen or food - there is no person. It is artificial to separate the plant from the sunshine or the person from oxygen – they are both one interaction. Traditional science breaks interactions and processes into their constituent parts. Gene’s first-person science places interaction as primary. When we begin with interaction, we can look at situations as something that are not external to our living.

In this way, our situations are not something external – a person who witnessed your argument with John will have a very different situational body-sense of the experience than you will. The strands or details of that body-sense will be relevant to the person themselves when it is opened up. The situational body knows our situations because it is our living in them and from them. This body-sense also implies our next step of living within that situation.

For plant-bodies this next step can be the usual pattern of eating or drinking, but when we add in the complexity that we encounter in the more elaborated animal body with the additions of the 5 senses and then add the human body which includes language and culture (the things that shape our interactions with others) – then the next step may be more and more complex than the usual patterns indicate.

We see Gene building the complexity of the body as it is sensed from inside. Beginning with the plant-body that is already an interaction in and with its environment. A body that already possesses information about its environment and its interaction with it. He then builds upon this kind of interaction by adding the complexities the animal-body (elaborated by the 5 senses) in addition or on top of the plant-body. When we add the complexity language and culture (our interactions with others) into the equation then we see the need for more elaborate ways of finding our next steps in complex situations. Old patterns given to us by our culture may no longer enable us to discover this kind of intricate next step.

The field of psychotherapy can illuminate these kinds of concepts. In Gene’s psychotherapy research, he discovered that people who are successful in therapy display a kind of inner interaction “It is something felt, but not yet known. It is sensed as meaningful, but not immediately recognizable. It is the … We now call it a felt sense”.

Gene went on to develop the Focusing process from this research. Focusing describes or points toward a process where we can have direct interactions with the felt sense. By first allowing the mind to quieten we can then begin to bring our attention into the centre of our body to notice what needs our attention. Perhaps there is an issue in our life we wish to work with, or we can sense into an unease in our body. Often it is a feeling or an emotion or a body sensation that comes first.

Gene tells us that we need to wait at this doorway until something more complex or global forms inside. This dimension of human experiencing is often missed or overlooked because it takes some time for this more complex/global felt sense to form. The felt sense is the bodies rendering of our plant/animal/human experiencing – it is the situational-bodies sense/expression of our complex experiential interactions.

Gene offers a wonderful explanation of the Focusing process on pages 27 and 28 of this article. I will not review this here, but I recommend that you read it.

My favourite part of this article is how Gene explore the process of writing poetry in relation to the kind of bodily interaction he is describing.

The … in Poetry

He begins by pointing towards a characteristic of therapy – “In therapy one must twist language, one must poetize in order to say some of it.” This illustrates how our usual language often doesn’t suffice when we are trying to articulate the complexity, the intricacy of our experiencing.

In previous times, this kind of bodily interaction was the remit of the mystics, the artists, and the poets etc. Gene Gendlin has now offered this possibility to everyone. Exploring the process of the poet can help illuminate this bodily interaction.

The poet has written six or seven lines of a poem and they are happy enough with them. The next line doesn’t come, so the poet rereads the lines, sensing into what needs to come next. A felt sense may form and the poet can refer to this formation to sense into what needs to come next. Many words and phrases may emerge, but they will be discarded if they will not offer what needs to come next, and what needs to come will be in the context of the lines already written. The poet resonates the words and phrases with the felt sense – this kind of interaction with the felt sense is very precise.

“The …. demands, it urges, it hungers, it insists upon, it knows, foreshadows, implies, wants … something so exact it is almost as if it were already said, and yet-no words... The … is full of words that are struggling to rearrange themselves into new phrases.”

If or when something new comes – the new phrase, the new line carries the meaning, the implying of the poem forward. But the felt sense does not disappear, rather it flows into the new line or phrase. It forms a new implying – the new line satisfies what the felt sense was, or more than what was there before, but a new implying emerges. This new implying may indicate the ending of the poem, or it may imply that more is needed. It may also imply a rewording or what went before.

“And we see again that the body knows the situation, the aspect of life the poet is trying to phrase. Else it could not know so exactingly that the suggested lines fall short.”

This kind of novelty, this kind of something new is what Gene calls “carrying forward”. It is not that the poet forgot the words that were needed – the words emerged freshly from all that went before. The situational body can offer something new – something fresh. The body does not just record our experiencing – it can also offer something new. Our past is not something external, it is something that can be operational in the present, and something new can emerge from that. The emergence of the felt sense allows us to live more deeply from our experiencing.

Gene often said that we can add Focusing to any human experiencing to make it better. This may seem like conceited claim, but I sense that what he was pointing towards is that we can appreciate our lived experience more fully if we add the situational sense of our experiencing. There is a courage that is required to pause at this edge of something that is felt but not yet known. But this courage is repaid by the possibility that something new may come that carries our experience forward.

3rd Assertion – The Body Implies Its Right Next Step

This third assertion is probably the most important for us today.

We live in cultures and structures that have become much more complex than earlier generations. The metaphors, the structures, the patterns, and the answers that guided living in the past no longer suffice to respond to the complexities of the modern world.

The kind of bodily implying that Gene describes has an important role to play in the creativity we can bring to the complexity of our lived experience.

I discovered Focusing at the age of 25 after I experienced a chronic illness that hospitalised me for 6 months and left me unable to work or function normally. All of my education hindered rather than helped me to navigate this complexity. I had no map for how to proceed – I certainly did not “know” how to reimagine my life in the face of this experience. I was stuck and anxious – trying to find rational answers to a human experience that demanded more than what rationality could offer.

The wonderful Phil Kelly (many people in the Irish Focusing Network will know Phil and all of her work) gave me a copy of Gene’s book “Focusing” and soon the next steps began to emerge from all that went before. My body knew my experiencing in a very different way to how my mind understood it – Focusing enabled me to use the precision of both.

In a similar way Gene points towards an example that Einstein outlines in his autobiography. Einstein tells us that “for fifteen years while working on the problem that led to the theory of relativity he was guided by “a feeling” of what the answer had to be.”

It is clear that Einstein moved forward from what he already knew about maths and physics – something new was implied from that knowing, but it took him 15 years to be able to express/articulate what was implied. This next step was felt – his body implied the next step. And like the poet, we can infer that the coming of the step that was needed to carry forward (provide the right next step) from came from all that went before.

“The body totals up the circumstances it has and then implies the next step, whether it is relativity or inhaling. This has not been well understood. The living body always implies its right next step.”

This is not a revolutionary call to discard all tacit knowledge and to throw away all of the patterns and structures of the past. Indeed, Gene warns us of the peril of discarding old forms because it is sometimes easier to do so. The novelty and creativity that bodily implying can provide a means of creating a map to guide us when our living is stuck or frustrated when the old maps no longer work or guide us. These new maps may contain elements of the old structures and patterns.

“When we don’t know what to do, we sense more than we can say. Once we pay direct attention to what we do sense, it is like a hunch: the …. knows more than we can say or do. Like Einstein, we have a “feeling,” an unclear sense for the solution we are looking for. Our sense of it is sufficient to make us reject all the available ways, although the new move that would carry this more into action does not yet exist”.

This quotation reminds me of my training in Philosophy – where I learnt over a period of time, that it is the questions we ask that are more important than any answers that may emerge. What Gene points towards in this article is that our bodies are an interaction with our environment and that the body implies it's right next step. This right next step emerges from the stoppage/stoppages (question/questions) in our living – if we sense into or open up what stops us then we can sense the more, the next step of where this stoppage (question) needs to go. And this next step is not an end in itself because it carries its own fresh implying forward with it.

We can begin to appreciate how Gene has built a sense of the human body that goes beyond static definitions to a developmental process that carries with it the implicit intricacies of our situational human living and experiencing.

Reflection:

So, the next time someone asks you to explain what Focusing is – what will you say?

I invite you to pause for a moment and sense how your body holds that question now….

In a recent discussion a colleague shared that trying to explain Focusing to a person who has never experienced it is like trying to explain what falling in love is like to someone who has never been in love. Of course, this is true to a large extent, but this should not stop us from trying to communicate the essence of the process to others.

Do Gendlin’s 3 assertions about the body assist you in trying to communicate something of the Focusing experience?

I will finish by outlining what I find helpful in this article:

- Many people will translate what we say into concepts they are familiar with and comfortable in using. So, if we say that Focusing is about the body and feelings, then they may translate that in a different way than we intend. Gendlin illustrates that he is talking about the body in a very different way than it has traditionally been understood, and that feelings are different to what many people understand because when we talk about feelings in this context, what we are pointing towards are the doorways to a more intricate and complex felt sense.

- The body that Gene is describing is the body as it is sensed from the inside. He offers us examples of how we can build the complexity of that body in a manner that goes beyond the traditional understanding of the body as a physical structure that is mainly a transportation system for the mind.

- This body “knows”, but it does so in a different way than the mind “knows”. As complex human beings living in a complex world, we need the precision of both kinds of “knowing”.

- The body that Gene explores in relation to how Focusing is possible, is an interaction with its environment. This interaction is evident in all of the phases of the human body that he describes i.e., the plant body, the animal body, and the human body. When we begin with interaction then we sense the world in a different way – we sense a world that includes us and our experiencing.

- The culture we live in spends so much time developing our capacity for conceptual thought but has forgotten its capacity for bodily knowing and carrying forward. This is not something we add onto human living – it is already there, and Focusing offers us the means to access and develop this capacity.

- Sensing into the questions is more productive than finding answers in our living. The questions can imply a deeper living – a way forward that the answers can never offer. There is a wonderful paradox implicit in the Focusing process, where it is the stoppages and questions that can offer us the possibility of living more creatively. For me there is a freedom and a hope in that possibility…

We can all become poets and live in a way that is full of creativity. When I teach Focusing to children – I tell them that I will offer them something that most adults don’t know – this peaks their attention. The younger children know Focusing in the marrow of their bones, but the sad thing is that we educate them out of it. So perhaps we can all become children again in this way…

[1] I will use quotes from Gene’s article in quotation marks to indicate that these are Gene’s words taken from the article being reviewed.

To read the complete article from the Gendlin Online Library click here![]()

AGM Report 2023

Report on the AGM 2023

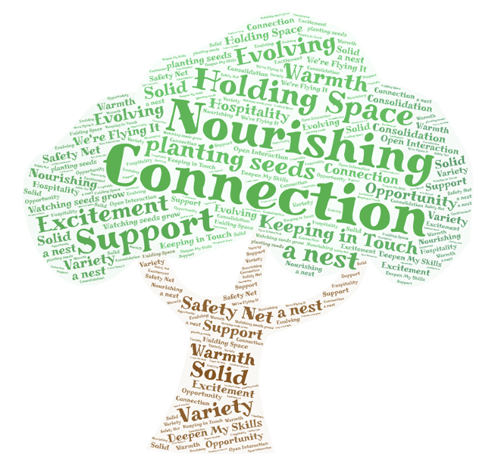

We are very grateful to all the people who attended the AGM on January 17th The interest and engagement of those who attended and their obvious commitment to developing the Network was very heartening. It was also lovely to listen as people spoke about what our Network means to them and what they value about it. We could list some of what they said, but Caroline Moore has created a far more inspiring record through illustrations like the one on the right. You will find others dotted through the report.

2022 in brief….

- Membership has grown.

- Online Focusing - over 40 sessions hosted by our Zoom volunteers.

- Marie McGuigan and Elaine Goggin have offered bi-monthly sessions on Focusing with Poetry.

- 3 Workshops online:

- Rennie Buenting – The approaches of Gene Gendlin and Anne Weiser Cornell

- Therese Ryan - The Enneagram and Focusing

- Mary Jennings – Saying More of What You Mean

- September in-person gathering of the Network at the Margaret Aylward Centre in Glasnevin. John Keane, Mary Jennings and Tom Larkin offered workshops.

- Practice sessions for new Focusers supported by Jayne Goulding and Kay McKinney

- 3 Newsletters created and distributed to members.

- New additions to resources on website thanks to members who suggested them

- Some of our members have successfully completed certification as Focusing professionals, trainers or co-ordinators.

- Focusing Advanced and Certification Weeklong hosted by The International Focusing Institute took place in Dublin in October attended by a number of members.

Current financial situation:

This year, we were able to hold an in-person gathering for the first time with a further event planned for March. While we welcome this new opportunity, it has brought new costs – primarily because of the need for insurance cover. This has meant that we ran a deficit for last year. Because our costs for the past two years were very low, we have a financial cushion which has allowed us to absorb this – but this will not be the case in future. For that reason the committee proposed the following changes to subscriptions:

Increase membership subscription for 2023 as follows

- Membership €30

- Profile membership €40

- For in-person gatherings - operate a sliding scale

- Regular price €35

- Modified price €30

Attendees may choose to offer a supporting contribution in excess of this if they wish.

The members who were present supported the proposal. New membership subscriptions will apply from January this year when renewals are due. You can renew your membership here.

Update on Zoom Sessions: Elaine Goggin outlined the results of the survey which was conducted in recent months. This showed a clear preference for reducing the number of online sessions to two a month and standardising when they occur. From February 2023, online sessions will take place on the 1st Wednesday of each month and on the 3rd Monday. The dates for February then, for example will be Wednesday, 1st and Monday, 20th. Our Network is an ever-evolving process, so we will keep this under review and invite feedback on how the new arrangements are working for you.

The survey also showed a high level of interest in regular “focusing conversations” which would provide an opportunity for members to discuss Focusing related topics of interest to them. If there are themes which members would like to explore, we invite you to contact us using the contact form on the website, which you will find here.

Lookig Forward

Our sincere thanks, again to everyone who attended. Your suggestions and contributions to the discussion have shaped an agenda for the committee over the coming months.

Following on from the AGM, the committee will be exploring:

- Follow up on Regional Focusing points

- How we might encourage and facilitate regular “focusing conversations” and occasional Members only workshops.

- Explore Unincorporated Association v Charity status

- Providing further opportunities for in-person gatherings

Update on progress since January:

A further

Some words shared about the Irish Focusing Nerwork on the night of the AGM.

Pause for Thought

Get people to practice pausing and they are on their way to learning Focusing

Mary Jennings

The word ‘pausing’ stands out. I’m reading the short evaluations written by the 8 participants in the Level One Focusing course that was offered to professionals working in services for residential/foster care child services in Ireland. In answering the question, what was the key learning for you in this course, again and again, phrases such as “the benefits of pausing and the simple, subtle ways this can be done” are repeated. My fellow trainers and I are surprised and a little intrigued at this outcome. We are not that sure that our course material was so skilfully designed to achieve this result! We were very much feeling our way, trying new ideas gleaned from different sources while ensuring that, at the end of the course, everyone would have a good foundation in the basic Focusing practices.

Mutual benefit in the experiment

Our proposition to the participants was clear: by participating in this free programme they would learn skills in the basics of Focusing. They could begin to use these in their work with children (generally those in the care of the State) and for their own self care as people in the frontline of often overstretched and under fire services. In return, as Focusing trainers we would get to try out different ways of teaching Focusing ; ways that involved the Community Wellness Focusing principles and practices of ‘learn a little, practice a little, pass it on a little, learn more. We would also get to incorporate what we, concurrently participants in a new Children Focusing training programme, were learning as we went along A big, but exciting agenda for an experimental course delivered over four half days. Pause. Yes, that feeling of excitement is there, bubbling away.

The Revolutionary Pause

And the concept of pausing, as presented and developed in this introductory course, seemed to have been what helped them quickly get a sense of this hard-to-describe Focusing process. When we slow down, pause, new possibilities have the potential to emerge. We can begin to sense for the more of what is there in any situation. We can allow a felt sense of ‘all that’ to begin to form. We can begin to live not from the surface of the situation, but from our own depths. Pausing is revolutionary! To be able to pause– to bring us down to earth for a moment – we need to practice it. It doesn’t come that naturally to everyone. Our working environments tend not to encourage it; sometimes we just have to manufacture it for ourselves.

Ways to pause

Having touched on some of these ideas, we invited our Level One participants to come up with ‘ways to pause’ in the course of the working day. To kick-start the conversation, Mary shared an idea she had come across that buildings have pauses built into them. Think about it. Porches, lobbies, corridors, so called’ landing strips’ in shopping malls are all designed to encourage you to pause as you transition from one place to the other; often from the outside to the inside…. It resonated. People began to see the possibilities in their own place of work. John confessed to being known as a ‘corridor stalker’; he deliberately uses the long corridors in the old building he works in just to pause and check in; to gather how he is inside as he prepares to meet the next person he is working with. Others might just pick up the phone, but the walk allows him the pause. Philipa, a smoker, banished with other smokers to a designated space outside, immediately saw new possibilities opening up in what is already a pausing space (even trying to convince us that this was a very good reason to smoke!). Jackie said, ‘take the breaks, go to the canteen rather than take a cup of coffee at your desk’. Anne recalled a phrase she had learned at a stress reduction class: ABBA – take A Break Between Activities. She could do that now with a renewed purpose, she felt. We were on a roll.

Guerrilla tactics

Other ideas, which we began to call ‘guerrilla tactics for pausing’ came tumbling out and include:

- Count to ten before reacting (old wisdom, now with a new understanding)

- Put a curfew on the cell phone during breaks/lunch/evening times

- When on the phone, say to the other person: “I am just writing down what you said so I get what you are saying (but really you are giving yourself time to pause)

- Become more comfortable with saying to people “ Can you leave that with me” or “I am not sure about that just now”(if even for a few moments) or putting back a question to the person –“What do you think” – all with the underlying intention of taking a pause for yourself.

In one way, these are all obvious, clichés even, but when they are done for the purpose of, as Andrew said, “… leaving space for what is not immediately obvious..”, then they take on a whole new dimension. Pausing-without-pausing now seemed possible within a busy environment that did not generally value - or even allow -it.

Practicing bring benefits

We invited the participants to take ‘practicing pausing’ as their homework for the week, including trying out some of the ideas generated on our first day together. Here’s what transpired for people who, at this stage had completed 3 hours of a Focusing course.

“I turned off the radio and cleared away the breakfast things and sat for a minute before I left for work – I just had a whole sense of the day that way”.

“Travelling with a child (a client) in the car, I just asked her ‘how are you… and waited. Normally I would be chatting and trying to create a distract and it seemed to give her just a little time to check for herself. It was amazing what a small pause like that could do”.

“I became much more comfortable with the silence between the young person and myself. He didn’t want to talk, so I created a pause deliberately. It was good. And I know there was stuff happening in that pause but without a strain”.

“I notice now that there is a pause built into the building, and just as you go in the door, you can connect to yourself for that moment”.

Pause for thought

As our course continued over the next three weeks, we covered many different aspects of Focusing – allowing the felt sense to form, listening compassionately, how the language we use can help create the right relationship inside, how to work with boundaries and safe spaces. There was something about spending the time right at the beginning working on pausing, why it’s important, what it can bring and how to do that in the hurly burly of a working day resonated. It really helped people to be more receptive to what Focusing could bring to them and to their work with children. Pause for thought indeed.

Bio

Mary Jennings is a Coordinator in Training with TIFI and she lives and works in Dublin. In 2011 Mary introduced Children Focusing training into Ireland and she is once again actively working on developing this form of Focusing for a wide audience. She has a particular interest in integrating Focusing practice with Thinking at the Edge (TAE), making core elements of TAE part of the way we teach and practice Focusing in everyday living.